A Machine for Burning Cities

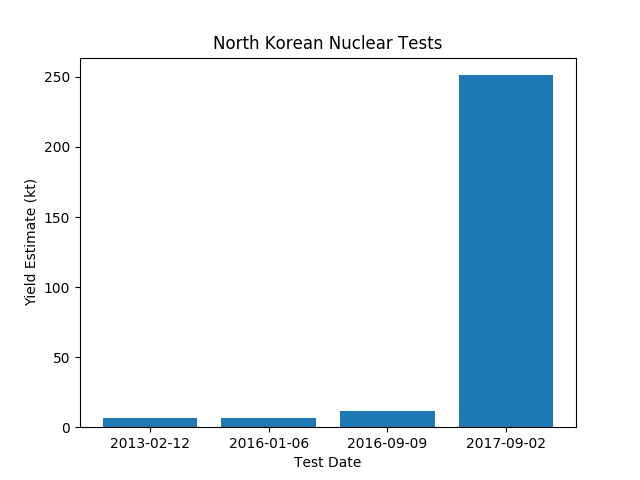

Nuclear weapons have returned to the forefront of public consciousness, fueled by coverage of North Korea's nuclear tests. News coverage has given the impression of steady improvement in the North Korean nuclear weapons program over the course of 4 tests from 2013 to 2017. For instance, here are the headlines from CNN for each test:

- February 2013: World leaders react to North Korea's nuclear test

- January 2016: North Korea announces it conducted nuclear test

- September 2016: North Korea claims successful test of nuclear warhead

- September 2017: Nuclear test conducted by North Korea, country claims; South Korea responds with drills

What is often overlooked in the news coverage is the yields of the tests.

Clearly this is anything but steady[0]. What happened? The last test was of a fusion bomb,

more commonly known as a thermonuclear or hydrogen[1] bomb.

Clearly this is anything but steady[0]. What happened? The last test was of a fusion bomb,

more commonly known as a thermonuclear or hydrogen[1] bomb.

We tend to ignore this distinction, talking about "nuclear weapons" instead of "thermonuclear weapons" or "hydrogen bombs". From Google Ngrams:

Even when the first hydrogen bomb was detonated, people tended to paint "nuclear weapons" with the same broad brush. The peak of public interest had already passed; we were already in the "atomic age". But the public was misled. The real dividing line in the history of warfare was not 1945, but 1952. Just ask the people who were there.

In 1945, J. Robert Oppenheimer was in Los Alamos, New Mexico leading the development of the atomic bomb. This position might seem strange for someone who, for most of his adult life, had been a committed pacifist. He would go on to be one of the foremost voices against the testing and use of nuclear weapons. A popular narrative is that he had been caught up in the fight against the Nazis and come to regret it. But in fact, he viewed the fission bomb much like a better machine gun or a faster airplane. It was, from the start, the prospect of the fusion bomb—or "super" as it was known at Los Alamos—that scared him. He called Edward Teller's work on the "super" genocidal—a term not used lightly by a Jew in 1945—and he so staunchly opposed Teller's work that Teller would end up testifying in favor of revoking Oppenheimer's security clearance years later. His opposition to nuclear weapons would center around lobbying for an international ban on the testing of hydrogen bombs. He failed.

Oppenheimer was right, about both the fission and fusion bombs. The fission bomb had as much explosive power as 10 air raids could deliver before. But the US conducted a lot more than 10 air raids. In total, Allied planes dropped 3.4 million tons of explosive on Axis powers—dwarfing the 2 atomic bombs by a factor of 100. Warfare would probably have been changed just as much by inventing, say, a significantly faster and lighter bomber. The "super", on the other hand, completely changed warfare. Despite Oppenheimer's efforts, the US built and tested it on November 1, 1952, in an operation codenamed Ivy Mike.

I have done my best to estimate the total explosive yield of bombs dropped in prior conflicts:

| Classification | Total Yield (kt) |

|---|---|

| WWI | <2[2] |

| Japan, Sino-Japanese War | <20[3] |

| Japan, Other WWII | <10[4] |

| Germany, WWII | <150[5] |

| Allied, WWII | 3,400[6] |

| US, Korea[7] | 635[8] |

| US, Fission tests pre Ivy Mike | 781[9] |

| USSR, Fission tests pre Ivy Mike | 102[10] |

| Total | <5,100 |

The yield of the "super" was 10,400 kilotons, far more than every bomb ever dropped before combined. It would take hundreds of fission bombs to match the devastation of WWII; a feat that could be accomplished in months instead of years, but more of a progression in the technology of warfare than a revolution. But thermonuclear weapons brought that down to minutes. That is the reality that gave us the Cold War, and has enforced the precarious peace of the last 70 years.

I worry that the public perception of "nuclear" weapons is too heavily colored by Hiroshima and Nagasaki. For all people decry the bombings, they take comfort in their constrained damage and the cities' relatively speedy recoveries. I have been to Hiroshima; the epicenter of the bombing is a nondescript office building now, and were it not for the 原爆ドーム (Atomic Bomb Dome) you would not know anything had happened. If a thermonuclear attack struck Washington, it would never rise again. The US Capitol, if such a thing even exists, would be a nondescript hill in Virginia[11].

I witnessed this phenomenon again when tensions flared between India and Pakistan, both "nuclear-armed countr[ies]" in the words of The New York Times. They—and nearly everyone else—elided the distinction between the nuclear capabilities of Pakistan and the thermonuclear capabilities of India. A nuclear war between them would be an unmitigated disaster for both of course, but the nation of India would continue to exist; the nation of Pakistan would not.

It's 70 years late, but we would do well to heed Oppenheimer's warning.

Title borrowed from Randall Munroe's book Thing Explainer.

- ^

Yield data is from the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Organization, which is run by the United Nations. The CTBTO estimate for the September 2017 test is higher than the most commonly cited figures in US media, which come from CIA estimates, but I consider these estimates suspect because their methodology is unclear and there is political motive to manipulate them. For more discussion of the various estimates and their uncertainties see here. Regardless of which estimate is used, the shape of the graph does not change much.

- ^

Some sources reserve the terms "thermonuclear" and "hydrogen" for staged fusion bombs. It is unclear whether the September 2017 test was of a relatively small staged bomb or a "fusion-boosted" fission bomb

- ^

This is a very rough estimate from reading Wikipedia's Strategic bombing during World War I. Regardless of the exact number, it was very low.

- ^

The only Japanese bombing figure I could find was in an encyclopedia arcticle, which claims Japan dropped 2 kt of explosive on Chungking, their largest target. I estimate this represents at least 10% of total Japanese bombs by yield dropped on China.

- ^

I couldn't find any numbers at all for Japanese bombing of non-Chinese targets, but given Japan's lack of a long range bomber and of attractive bombing targets, it can't be very high.

- ^

According to THE BOMBING OF FRANCE 1940-1945 EXHIBITION, p. 7, Germany dropped 74 kt of explosive during the Battle of Britain. I couldn't find any totals for German bombing of other European countries, but they seem to have been much lower, due to their shorter duration and Germany's ability to field ground troops. I am conservatively estimating that at least half of German bombs by yield were dropped on Britain.

- ^

This number is based on a public data.mil dataset.

- ^

This includes bombing after Ivy Mike but before the Korean war ended in 1953.

- ^

The Destruction and Reconstruction of North Korea, 1950 - 1960, p. 1

- ^

Summed from the pre-Ivy tests listed on Wikipedia.

- ^

Sum of the 3 nuclear tests conducted by the USSR in 1949 and 1951.

- ^

Specifically, the Mount Weather Emergency Operations Center, which is the designated staging point for immediate continuity of government plans. It is not intended as a permanent base, but I assume that the US Government would not quickly move without a clear alternative.